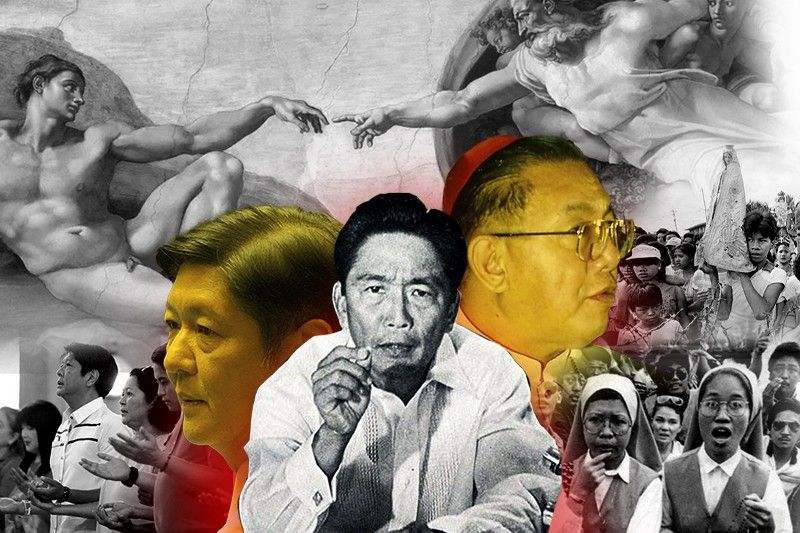

Five days before the 2022 elections, framed by many as the most crucial since the 1986 snap polls, over 1,200 Catholic bishops, priests and deacons declared their support for then-Vice President Leni Robredo’s bid for Malacañang.

This unprecedented move came just a day after homegrown Christian sect Iglesia ni Cristo announced that they would be backing Robredo’s rival Ferdinand Marcos Jr., the son and namesake of the dictator that the Catholic Church helped oust 37 years ago in what was known as the People Power Revolution.

Msgr. Melchor David, one of the convenors of Clergy for the Moral Choice that supported Robredo, said then that the Church “sorely needed” to show its concrete participation in what he called “a battle between true and false.”

Even top clerics framed the last elections this way.

Kalookan Bishop Pablo Virgilio David, president of the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines, said in a homily during a Mass a month before the polls “that the main issue in the field of politics has to do with spiritual and moral: the issue of ‘truth’ and ‘falsehood.’“

When El Shaddai’s Bro. Mike Velarde raised the hands of Marcos Jr. in an apparent endorsement, Most Rev. Bishop Teodoro Bacani was quick to disown it. Bacani, in an interview with ABS-CBN’s Teleradyo, said it was “downright wrong … because we know their records and to this day, they have not apologized [for] the anomalies of the past.”

Lingayen-Dagupan Archbishop Socrates Villegas went as far as calling Marcos Jr. a “threat” in an interview with Rappler due to the then-presidential candidate’s distortion of facts surrounding his father’s brutal martial rule.

The CBCP, itself, in a pastoral letter denounced “radical distortions” about Martial Law and the 1986 People Power Revolution as it called on Catholics to “not give up on our search and defense for truth.”

Shepherds of the over 85 million Catholics in the country spoke clearly about the elections and what they believed was at stake — and yet their flock did not seem to have heeded their call.

On the evening of May 9, 2022, as partial and unofficial results poured in at lightning speed, it became apparent that the Philippines would have another Marcos as president.

The electoral exercise again put in doubt whether there is a Catholic vote and what the Church’s place is in a society that it has at times found itself at odds with — from the Reproductive Healh Law to the “war on drugs”, which was popular despite, and because, of its brutality.

‘Prophet of denunciation’

Six days after the 1986 snap elections that pitted Marcos Sr. and Corazon Aquino against each other, Catholic bishops in the Philippines rendered an indictment on the conduct of the polls, which they said were “unparalleled in … fraudulence.”

“A government that assumes or retains power through fraudulent means has no moral basis,” the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines said in a statement on February 13, 1986.

The bishops urged their flock to “speak up” and organize to “repair the wrong … in a peaceful, non-violent way.”

Some two weeks after this, Manila Archbishop Jaime Cardinal Sin went on Church-run Radio Veritas to call on Filipinos to protect defectors Juan Ponce Enrile and Fidel V. Ramos from government troops as they holed up in Camp Aguinaldo.

This marked the beginning of the peaceful and non-violent repair of the wrongs done by the decades-long rule of Marcos Sr. that ultimately led to his fleeing Malacañang for Hawaii assisted by the United States and the installation of the widowed Aquino as president.

In an interview in London with Independent Catholic News just under two weeks after the peaceful revolution, Sin said he advocated for political change in the Philippines because of morality and not politics.

“It was a risk, that a pastor has to be a prophet of denunciation and also a minister of reconciliation,” he was quoted as saying.

Sin’s role as a prophet of denunciation continued beyond the People Power Revolution.

In 1991, he told Aquino not to endorse any presidential candidate as doing so was “an insult to the intelligence of Filipinos.” He was among the leaders of a protest in Luneta Park, where half a million people opposed Charter change in 1997.

A decade later, he called for the removal of another plundering president, Joseph Estrada, in yet another peaceful demonstration on EDSA.

Post-Sin era

Sin died in 2005 and with his passing came the end of an era when the Church actively dabbled in politics.

“Nobody else could replace Cardinal Sin,” said Jayeel Cornelio, a professor at the Jesuit-run Ateneo de Manila University who studies religion, in an email to Philstar.com.

“[He] was a product of his time. The big enemy then was Marcos and the entire regime. The only institution that could match the regime in terms of reach and influence was the Catholic Church.”

Seven years after what was called EDSA Dos, it was reported by GMA News Online that Manila archdiocese vice chancellor Fr. Sid Marinay said the CBCP recognized the error of the uprising, which he said “weakened political institutions.”

“The kind of political activism the CBCP is trying to espouse at this point in Philippine history is at the service of the stability of our political institutions to be able to solve political problems and prevent political crises,” Marinay said in an article that was supposedly posted on the Manila archdiocese’s website.

“This emphasis on making the political institutions strong by promoting the ‘rule of law’ serves as a grammar that can help accurately interpret the language of the CBCP at this point in Philippine history, and the thread that coherently links all of the CBCP statements from 2004 to 2008, the post Cardinal Sin era of the Catholic Church in the country.”

This shift in the role of the Catholic Church in political affairs was also documented in a leaked diplomatic cable where former CBCP president Archbishop Fernando Capalla was quoted as saying that “Sin went too far into politics on occasion to the detriment of the Church.”

So when the country was plunged into political turmoil after allegations of electoral fraud surfaced against then-President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo — who later staged a successful political comeback and is currently Pampanga representative at the House of Representatives — the CBCP said in a carefully crafted statement in 2005 that they “do not demand her resignation … yet, neither do we encourage her to simply dismiss such a call from others.”

Watershed moment

While the Church in the Philippines after Sin has generally refrained from entering into political affairs, it still makes its voice heard when it comes to certain issues such as contraception as was seen during its fierce campaign against the reproductive health law.

The CBCP took a hardline stance against the law which was identified as a priority by then-President Benigno Aquino III, the son of the president whom the Church helped install following the 1986 revolution.

So when the country was plunged into political turmoil after allegations of electoral fraud surfaced against then-President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo — who later staged a successful political comeback and is currently Pampanga representative at the House of Representatives — the CBCP said in a carefully crafted statement in 2005 that they “do not demand her resignation … yet, neither do we encourage her to simply dismiss such a call from others.”

Watershed moment

While the Church in the Philippines after Sin has generally refrained from entering into political affairs, it still makes its voice heard when it comes to certain issues such as contraception as was seen during its fierce campaign against the reproductive health law.

The CBCP took a hardline stance against the law which was identified as a priority by then-President Benigno Aquino III, the son of the president whom the Church helped install following the 1986 revolution.

There were massive protests initiated by the Church hierarchy against the reproductive health law. Catholic clergymen called on the faithful to not vote for politicians who were supposedly not following Church teachings and Aquino III was threatened with excommunication.

Despite the Church’s stiff opposition, the reproductive health law was enacted.

“The RH Bill was a watershed moment,” said Cornelio, the Ateneo de Manila University professor. “That effectively called into question its power over legislation. It took a president like [Aquino III] to push back on the Catholic Church hierarchy.”

“After him, every president has sidelined the Church leadership in significant ways. [President Rodrigo] Duterte cursed its bishops, and in Marcos Jr.’s time, none of them seem to have the president’s ears.”

Silent Church

In 2017, the CBCP denounced the “reign of terror” brought about by the killings in the course of the Duterte administration’s “war on drugs,” which prompted Malacañang to call the organization “out of touch.”

What followed was a barrage of vitriolic attacks from Duterte on the Church — ranging from allegations of sexual abuse to an outright call to kill bishops — which Msgr. David admitted had a big impact on its popularity and influence.

“Sad to say, some of our people [were] easily carried away by those speeches,” Msgr. David told Philstar.com in an interview. “Even to the point that Filipino people make statements such as, ‘The Church should stop yapping because it has not done anything about drugs.’”

Save for individual prelates speaking up against Duterte’s tirades, the Church hierarchy largely kept its silence until 2019 when it issued a pastoral statement that asked Catholics for their forgiveness.

“Forgive us for the length of time that it took us to find our collective voice. We too needed to be guided properly in prayer and discernment before we could guide you,” the CBCP said.

For Thomas*, a lay Catholic who was in his 20s during the 1986 EDSA Revolution, the Church has largely been silent then and now.

“The Church then, as it is now, was mainly silent during the peaceful years of ML and only became enraged after Ninoy’s death, after which it became a spearhead and a rallying point through all the upheavals that followed,” said Thomas, now a retired engineer.

Msgr. David, however, said it is a “misnomer or mislabelling” to say that the Church’s influence in the country has weakened.

“When the Philippines was put into complete lockdown, have you ever tried to see or look at figures how many availed of the online services of the Catholic Church?” he said. “Whenever the Filipino people experience social or political issues, don’t they always ask: ‘What will the Church say?’”

Professor Cornelio said that while Church leaders may not necessarily be reflecting the political sentiments of the general public, they still hold some influence.

He explained that this is because Catholics do not like that their priests use the pulpit for politics, but Msgr. David said they only provide “moral guidelines.”

“Politics happens to be one of the areas where the Church has to exercise its leadership to guide the people in making not only rightful choices, but also moral choices,” Msgr. David said.